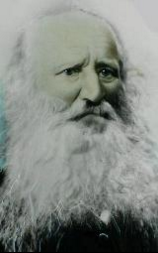

John Lidiard 14.09.1789 ~ 09.01.1876

|

A ship boy in Nelson's navy, a sailor, Jack Tar, a whaler. A lone white man in a land of warriors, the adventures of a father, a husband, a settler, and a man who witnessed the birth of a nation.

The beginning John Lidiard was born in Deptford, England, in 1789. Deptford prospered as home to the Royal Navy Dockyards where wooden warships were built, victualed, and repaired under the shadow of London on the banks of the River Thames. Admirals lived in beautiful homes in Albury Street, but sailors were more at home in riverside taverns. Press gangs roamed cobbled streets in search of able bodied men to abduct and force into a life at sea. Young children worked as chimney sweeps or in damp, dangerous factories for twelve hours a day. Yet, true hardship was reserved for the most destitute, those who languished in poor houses or prison hulks waiting to be transported to a fate worse than jail, on the other side of the world. |

|

The river Thames was swamped with thousands of lighter boats ferrying crew and cargo between the ships and wharves. River pirates salvaged what they could when boats sank, and pilfered the rest from warehouses. The town's seafaring history was long and colourful. Sir Walter Raleigh, Sir Francis Drake, and Captain James Cook had all set out from Deptford. On 11 October 1789, John Clark Lidiard was baptised at the ancient parish of St Nicholas, under the patron saint of sailors, protected by the skull and crossbones on its gate. For a boy there was but one way out of Deptford and so John began his career as a Royal Navy volunteer at the Battle of Copenhagen in 1801.

Ships volunteers were young boys who turned to a life at sea for their apprenticeship, education, and a chance to earn a living. They entered the navy through port flagships or the Marine Society, learning the ropes on the Thames before being assigned to ships as servants to officers or senior seamen. |

|

Some were sold into service by their parents to repay debts or because it was one less mouth to feed. Many were drawn to the romance of adventure, but life at sea was often brutal. During battle they raced between decks with gunpowder hidden beneath their clothes trying not be maimed or killed by a wayward spark.

John was eleven years old at the Battle of Copenhagen. One ship at the battle, HMS Blanche, was built and manned at Deptford before sailing to join Sir Hyde-Parker’s fleet in Yarmouth bound for the Baltic. Perhaps John Lidiard was a boy on this ship. The battle was hot work at close quarters and hundreds of men were killed on both sides. The English came away from Copenhagen resounding victors. All but two of the Danish fleet were burned, captured, or destroyed. During battle one of Admiral Hyde Parker’s officers, Horatio Nelson, placed his telescope to his blind eye. Unable to see the Admiral's signal to retreat, he 'turned a blind eye' and continued to blast his way to victory |

A man at sea

By 25, John Lidiard had risen to be Captain of the Maintop. This post was reservered for only the most reliable and agile of the able bodied seamen. To be in charge of a crew in the maintop required a person of great skill and athletic ability. Men who worked in the upper rigging performed the most demanding work aloft. Although John had worked his way literally to the top of the ship, he still ranked as a rating, well below the officers. He worked hard for his pay and to earn his share in the prize money of captured enemy ships. During the blockade of Boston, John served aboard the 74 gun razee, HMS Majestic.

When British ships began intercepting American merchant vessels and taking their men, the war of 1812 was declared. Pride of the US Navy were the super frigates USS Constitution and USS President. Britain desperately wanted to capture one of these to rally the English at home, and at sea.

In January 1815, HMS Majestic led a small squadron of British vessels that would eventually run the USS President down as she tried to escape from the harbour during a snowstorm. Having lost a fifth of her crew in the battle, USS President was defeated and taken back to England, the ultimate high seas trophy, albeit severely damaged when a storm hit the fleet after her capture.

By 25, John Lidiard had risen to be Captain of the Maintop. This post was reservered for only the most reliable and agile of the able bodied seamen. To be in charge of a crew in the maintop required a person of great skill and athletic ability. Men who worked in the upper rigging performed the most demanding work aloft. Although John had worked his way literally to the top of the ship, he still ranked as a rating, well below the officers. He worked hard for his pay and to earn his share in the prize money of captured enemy ships. During the blockade of Boston, John served aboard the 74 gun razee, HMS Majestic.

When British ships began intercepting American merchant vessels and taking their men, the war of 1812 was declared. Pride of the US Navy were the super frigates USS Constitution and USS President. Britain desperately wanted to capture one of these to rally the English at home, and at sea.

In January 1815, HMS Majestic led a small squadron of British vessels that would eventually run the USS President down as she tried to escape from the harbour during a snowstorm. Having lost a fifth of her crew in the battle, USS President was defeated and taken back to England, the ultimate high seas trophy, albeit severely damaged when a storm hit the fleet after her capture.

|

John is then believed to have transferred to HMS Bellerophon, one of the Royal Navy's most famous ships. Known by sailors as ‘Billy Ruff’n’, she was in action at the Glorious First of June, the Battle of the Nile, and the Battle of Trafalgar. In 1815, with John Lidiard in her crew, she took on her most famous passenger of all. Leaving Plymouth in May, HMS Bellerophon sailed to Rochefort and while there, the French General, Napoleon, having been defeated at Waterloo, was taken on board by Captain Maitland. Napoleon was given protection by England and taken back to Torbay where word quickly spread that the little general was on board.

|

Thousands crowded into boats and surrounded the ship, desparate to catch a glimpse. In the evening, when Napoleon appeared on deck, the throngs of onlookers went wild and in the scramble to get even closer, boatloads of spectators sank. No one was allowed on or off HMS Bellerophon and eventually, to stop the mayhem, she sailed for Plymouth where similar scenes awaited. When Napoleon was transferred to HMS Northumberland, Billy Ruff’n's crew was taken to Sheerness and paid off.

As far away as possible

With the French/English war now over, Britain's Royal Navy was reduced from 145,000 to 19,000 men. Thousands flooded the work force but there were few jobs to fill. In 1817, London was gripped by fever. With little chance of earning money in a sick and gloomy city, John turned back to a life at sea. For several years, sealing and whaling ships had been making speculative voyages to the southern fisheries, often returning with lucrative cargoes of oil and pelts for the London market. It was a long, risky venture but men were enticed by the promise of a good return.

As far away as possible

With the French/English war now over, Britain's Royal Navy was reduced from 145,000 to 19,000 men. Thousands flooded the work force but there were few jobs to fill. In 1817, London was gripped by fever. With little chance of earning money in a sick and gloomy city, John turned back to a life at sea. For several years, sealing and whaling ships had been making speculative voyages to the southern fisheries, often returning with lucrative cargoes of oil and pelts for the London market. It was a long, risky venture but men were enticed by the promise of a good return.

|

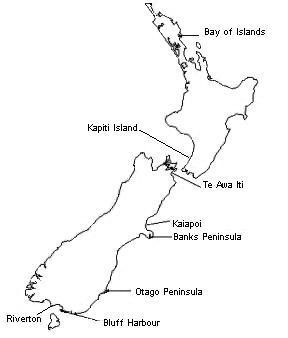

.On 11 August 1817, John Lidiard joined the crew of the whaling ship Indian under Captain William Swain, of America, and set sail for the South Seas. Eight months passed before Indian reached New Zealand's Bay of Islands, arriving with Foxhound, another London whaler. Early whale ships replenished at the Galapagos Islands and throughout the Pacific before sailing with caution into New Zealand waters. Captains and crew were wary of the native New Zealanders; the burning of the Boyd and massacre of its crew a few years earlier still on every sailor’s mind.

|

|

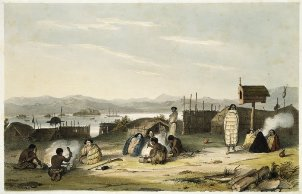

As ships arrived, Maori in waka paddled out to surround them, each world sizing the other up. Whalers needed water, pork, potatos, and wood for repairs. Tribal Maori were out for trade, very quickly realising they could gain advantage over rivals with the skills and items visiting ships had on board. On John's first night at the Bay of Islands Captains Swain and Watson were joined on board Foxhound by missionaries Kendall, King, and Hall. New Zealand’s first mission station was only three years old, and visiting ships were still relatively few and far between.

The missionaries sought news and supplies from the outside world while the whaleship masters were eager to hear how they could replenish their ships. John and his crewmates found themselves in very different company. New Zealand's native men where physically big and strong, and they displayed sharp inquisitive minds. They were good humoured until offended and worked hard as crew when they joined whalers. |

The women, despite being treated as currency, made the best of their situation. Full of song and laughter, many whalers formed close attachments to Maori girls and would seek them out on returning visits to the Bay. They stayed on the ships while in port and some remained on board for the voyage to the fishing grounds.

The next port forIndian was Sydney Cove where John and his crew mates unloaded a cargo of Porter’s Ale, slop clothing, and soap. In 1818, convicts still outnumbered settlers in the prison colony but business and enterprise were beginning to develop. The Sydney Gazette reports that three weeks after arriving in Sydney Cove, the crew of Indian mustered onshore and made their way back to their ship to resume their journey. When the men boarded the ship they became "unruly" and chief officer Silas West was forced to call for Captain Swain who was ashore making preparations to leave. After speaking to his chief officer, and noticing that the men were in a "very untowards state", Captain Swain called one of them to the quarterdeck to explain their grievance. Such was the ire of his crewmates, that 10 or 12 followed him to the quarterdeck, and Captain Swain quickly found himself up against a very unhappy crew. Swain would later tell police that the men were insulting, disrespectful, and abusive, and that some demanded their immediate release from the ship. One man in particular commanded their release and Captain Swain ordered him from the quarterdeck. When the man refused to budge, Captain Swain pushed him and a scuffle broke out, during which the captain was reportedly struck. The tussled culminated in Captain Swain being himself driven forward by the men. After the captain managed to extricate himself from the situation, the police were called onboard to arrest the three principal offenders - Luke Wade, William Dally, and John Liddiard.

John and his crewmates would most likely have spent a night or two in the notorious George Street jail, until they appeared in court. They were committed for trial on a charge of mutiny for the assault on Captain Swaine on the quarterdeck of the ship Indian. Until the court transcripts are uncovered, what happened next remains a mystery. However, on 22 September, Luke Wade, William Dally, and John Liddiard sailed from Sydney Cove on Indian. They had survived a charge of mutiny.

After almost two years at sea hunting whales, John arrived home to England in July 1819. The crew were paid off and once more with pockets jingling, John headed for London.

A savage life

Indian returned to the South Seas just two months later but John was not on board. He had transferred to another whaler,Vansittart, commanded by Captain Thomas Hunt. On Vansittart, John was now a boat steerer, so his cut was higher than that of an ordinary seaman. With him from Indian went Thomas Davis, James Sawyer, and Luke Wade. John and his crew mates set out from Deal in January 1820 bound once again for the South Seas, and eight months later Vansittart arrived in Sydney having taken on 100 barrels of oil during her voyage out.

After Sydney, Vansittart called at the Bay of Islands where she fell in with Cumberland. If life as a Jack Tar in the navy had been hazardous, it was little better on whale ships. The whales always suffered the worst fate, but men were often tangled in ropes and dragged to their death. Out for the kill, whalers gave chase in small whaleboats sometimes rowing for miles in pursuit of a whale. Boat crews became disoriented as they lost sight of their ship and drifted off into an endless expanse of unforgiving ocean with no hope of survival. When a whale was killed it was towed back to the whale ship and stripped of its blubber which was boiled down into oil and kept in barrels. No sooner had the process finished when another whale was spotted and off they'd go again.

The next port forIndian was Sydney Cove where John and his crew mates unloaded a cargo of Porter’s Ale, slop clothing, and soap. In 1818, convicts still outnumbered settlers in the prison colony but business and enterprise were beginning to develop. The Sydney Gazette reports that three weeks after arriving in Sydney Cove, the crew of Indian mustered onshore and made their way back to their ship to resume their journey. When the men boarded the ship they became "unruly" and chief officer Silas West was forced to call for Captain Swain who was ashore making preparations to leave. After speaking to his chief officer, and noticing that the men were in a "very untowards state", Captain Swain called one of them to the quarterdeck to explain their grievance. Such was the ire of his crewmates, that 10 or 12 followed him to the quarterdeck, and Captain Swain quickly found himself up against a very unhappy crew. Swain would later tell police that the men were insulting, disrespectful, and abusive, and that some demanded their immediate release from the ship. One man in particular commanded their release and Captain Swain ordered him from the quarterdeck. When the man refused to budge, Captain Swain pushed him and a scuffle broke out, during which the captain was reportedly struck. The tussled culminated in Captain Swain being himself driven forward by the men. After the captain managed to extricate himself from the situation, the police were called onboard to arrest the three principal offenders - Luke Wade, William Dally, and John Liddiard.

John and his crewmates would most likely have spent a night or two in the notorious George Street jail, until they appeared in court. They were committed for trial on a charge of mutiny for the assault on Captain Swaine on the quarterdeck of the ship Indian. Until the court transcripts are uncovered, what happened next remains a mystery. However, on 22 September, Luke Wade, William Dally, and John Liddiard sailed from Sydney Cove on Indian. They had survived a charge of mutiny.

After almost two years at sea hunting whales, John arrived home to England in July 1819. The crew were paid off and once more with pockets jingling, John headed for London.

A savage life

Indian returned to the South Seas just two months later but John was not on board. He had transferred to another whaler,Vansittart, commanded by Captain Thomas Hunt. On Vansittart, John was now a boat steerer, so his cut was higher than that of an ordinary seaman. With him from Indian went Thomas Davis, James Sawyer, and Luke Wade. John and his crew mates set out from Deal in January 1820 bound once again for the South Seas, and eight months later Vansittart arrived in Sydney having taken on 100 barrels of oil during her voyage out.

After Sydney, Vansittart called at the Bay of Islands where she fell in with Cumberland. If life as a Jack Tar in the navy had been hazardous, it was little better on whale ships. The whales always suffered the worst fate, but men were often tangled in ropes and dragged to their death. Out for the kill, whalers gave chase in small whaleboats sometimes rowing for miles in pursuit of a whale. Boat crews became disoriented as they lost sight of their ship and drifted off into an endless expanse of unforgiving ocean with no hope of survival. When a whale was killed it was towed back to the whale ship and stripped of its blubber which was boiled down into oil and kept in barrels. No sooner had the process finished when another whale was spotted and off they'd go again.

|

Vansittart made several calls to the Bay of Islands during this voyage and while there in May 1821 John and his shipmate Luke Wade left the ship after falling out with chief mate William Whippy. As the only Europeans living at Kororareka, the men were under the jurisdiction of Ngati Manu chief, Pomare. Pomare was considered by the mission as one of the most important men in the Bay and second only to Hongi Hika in instilling fear in the hearts of the enemies he chose to wage war against. Pomare was also considered somewhat of an expert in the art of preserving his victim's heads which were sought after as items of trade by visiting whalers. |

Chief Pomare quickly understood the benefit of having European residents among his tribe and was keen to increase the number of ships that anchored in his area. Potatoes were cultivated specifically for trade and muskets and gunpowder were highly prized. In order to maintain and fix muskets, and so as not to be duped by traders offering faulty guns, European residents were enlisted to act as go-betweens. Men who lived among Maori came to be known as Pakeha-Maori, leaving behind their own culture to either embrace Maoridom or be dragged into it. Some men were kept as slaves, some escaped as soon as they could find a ship that would take them, and others displaying courage and a genuine interest in Maoridom rose to the status of chief.

Two years after leaving their ship at the Bay of Islands, Luke Wade was enlisted as a servant for the Wesleyan Mission station established in Whangaroa. John continued to live at Kororareka, most likely in a small wooden hut just off the beach and probably with a woman closely linked to his chief protector.

The turning tide

By the late 1820's, the easy relationship between the whalers and the missionaries had disintegrated due mainly to musket trading. The mission went to great lengths to avoid trading in weapons which at times saw them facing starvation. They were also morally repulsed by the polygamous relationships the residing seamen indulged in with Maori women. The sailors, at the mercy of the chiefs for survival, lived by their laws and customs. Some took part in skirmishes or fought in inter-tribal wars, and many witnessed frequent acts of cannibalism. Living as a Pakeha Maori was a difficult life and most lasted only a matter of months. John, however, was still living at Kororareka six years later when an incident occurred that saw the mission and whalers act in a rare display of unity.

Two years after leaving their ship at the Bay of Islands, Luke Wade was enlisted as a servant for the Wesleyan Mission station established in Whangaroa. John continued to live at Kororareka, most likely in a small wooden hut just off the beach and probably with a woman closely linked to his chief protector.

The turning tide

By the late 1820's, the easy relationship between the whalers and the missionaries had disintegrated due mainly to musket trading. The mission went to great lengths to avoid trading in weapons which at times saw them facing starvation. They were also morally repulsed by the polygamous relationships the residing seamen indulged in with Maori women. The sailors, at the mercy of the chiefs for survival, lived by their laws and customs. Some took part in skirmishes or fought in inter-tribal wars, and many witnessed frequent acts of cannibalism. Living as a Pakeha Maori was a difficult life and most lasted only a matter of months. John, however, was still living at Kororareka six years later when an incident occurred that saw the mission and whalers act in a rare display of unity.

|

In early January 1827, John was sawing boat planks for Captain Duke of the whale ship Sisters, when a brig sailed into the Bay. She anchored close to Sisters, and another whaler Harriet which was replenishing at Kororareka before returning to England. John watched as Duke rowed out and brought the vessel in, then took to his own boat with some local Maori and headed out to the ship. Looking around on board, John saw several men in military uniform, all on sentry, but nothing was shipshape. He lost no time in getting over to the Sisters to ask Captain Duke and first mate Philip Tapsell what they thought of the ship. A note was slipped off the brig and the convict captain confessed to the mutiny but was allowed to return to Wellington. Duke wasn't keen to become involved in a dangerous confrontation with a ship full of bloodthirsty villans, but Tapsell and Lidiard went among the crew and rallied the men to recapture the pirated ship.

|

In 1823, Henry Williams had established a new mission station at Paihia directly across from Kororareka. He'd crossed paths before with John Lidiard as a midshipman aboard HMS Endymion in the squadron that captured USS President. Williams urged the whale ship captains to use their great guns against the mutineering convicts. Tapsell, who like John had been a sailor all his life, took careful aim at the Wellington, and sent a shot into her quarter before a second shot took out her top rigging. John was sent ashore to alert the Maori, evidently with much success, as the convicts agreed only to surrender if they could go ashore and on the condition the musket-armed natives surrounding the ship in canoes would not harm them. The demands were agreed to and many convicts fled ashore causing great concern for the mission who were unable to protect themselves against desparate criminals. Captain Duke enlisted John to have the Maori find them and one by one they were recaptured, secured, stripped, taken back to the ship, and exchanged for muskets and casks of gunpowder. A few escaped, one of which John sighted many years later living "more as Maori than European" in Port Nicholson, coincidently now known as Wellington. Five convicts already sentenced to death before the mutiny, ended their lives in the gallows after being taken back to Sydney. The large crowd booed as the men dropped, many sympathising with them for showing no violence during the mutiny and being tricked into surrender.

The following year Te Whareumu, known as King George, a good friend to the Europeans and current chief of Kororareka, was killed while trying to avenge the death of Pomare's son. Left under the protection of a less powerful chief, the Maori and European residents were susceptible to plundering by competing tribes from the northern Bay of Islands. About this time, the original settler John Lidiard, perhaps with nothing left to stay for, joined a ship and sailed away from the people with whom he'd made his home for so many years.

Southward bound

Almost all ships trading off the coast of New Zealand called at the Bay, so word quickly spread of developments in other areas of the country. The latest news was the value of flax, and in Sydney vessels were preparing to head for Cook Strait between the North and South Islands in search of the new commodity. John may have acted as an interpreter on a trading ship as after so long living among Maori, his knowledge of their culture and language would have been invaluable to captains seeking flax. However he ended up moving south, if he was hoping to find a more peaceful place to settle, he sailed right into the wrong place.

In 1829, former sealer Jacky Guard was living in the South Island’s Marlborough Sounds selling whalebone to passing ships, of which there were plenty, all in search of flax. Guard’s life was not easy, with local Maori often harassing him, but it was a chief from the Kapiti region who would turn everyone’s world upside down. For several years, the South Island's Ngai Tahu people were embroiled in their own revenge fueled inter-tribal war, which came to be known as the Kai Huanga Feud. The war had almost decimated the feuding relatives, but they quickly set aside their differences when northern warlord Te Rauparaha made his intentions clear.

The following year Te Whareumu, known as King George, a good friend to the Europeans and current chief of Kororareka, was killed while trying to avenge the death of Pomare's son. Left under the protection of a less powerful chief, the Maori and European residents were susceptible to plundering by competing tribes from the northern Bay of Islands. About this time, the original settler John Lidiard, perhaps with nothing left to stay for, joined a ship and sailed away from the people with whom he'd made his home for so many years.

Southward bound

Almost all ships trading off the coast of New Zealand called at the Bay, so word quickly spread of developments in other areas of the country. The latest news was the value of flax, and in Sydney vessels were preparing to head for Cook Strait between the North and South Islands in search of the new commodity. John may have acted as an interpreter on a trading ship as after so long living among Maori, his knowledge of their culture and language would have been invaluable to captains seeking flax. However he ended up moving south, if he was hoping to find a more peaceful place to settle, he sailed right into the wrong place.

In 1829, former sealer Jacky Guard was living in the South Island’s Marlborough Sounds selling whalebone to passing ships, of which there were plenty, all in search of flax. Guard’s life was not easy, with local Maori often harassing him, but it was a chief from the Kapiti region who would turn everyone’s world upside down. For several years, the South Island's Ngai Tahu people were embroiled in their own revenge fueled inter-tribal war, which came to be known as the Kai Huanga Feud. The war had almost decimated the feuding relatives, but they quickly set aside their differences when northern warlord Te Rauparaha made his intentions clear.

|

With one eye on Ngai Tahu’s precious greenstone, Te Rauparaha annihilated the sub-tribe Ngati Kuri at Kaikoura, then set his sights on Ngai Tahu’s main fortified pa at Kaiapoi, just north of where Christchurch city stands today.

Te Rauparaha visited Kaiapoi pa and while there an event occurred that would have dire consequences for the entire southern tribe. Several of Te Rauparaha’s Ngati Toa chiefs were killed when fighting broke out inside the pa during trade negotiations. It was a bitter blow for him. He gathered his men and returned home filled with rage to plot his revenge and wait until the time was right to strike. That time soon came with the help of a European captain and his ship. What happened would become one of the darkest events in New Zealand history. |

One night to change them all

By 1830, Guard had established one of the first shore whaling stations in New Zealand. Migrating whales came into Cloudy Bay and were close enough in for men to take to their whale boats, frantically row out to the whale, kill it, and tow it back to shore. Whalers settled at Cloudy Bay for the whale season where they worked hard and played hard.

Several trading ships were in the area seeking flax but finding it increasingly difficult to secure a cargo. The Maori either refused to trade or had upped the price expected in return. Captains become frustrated at the prospect of returning to Sydney empty with no profit and the prospect of a mutinous crew. Into the mix of difficulty acquiring flax and a warrior chief bent on revenge, sailed Captain John Stewart and his brig Elizabeth. In return for a cargo of flax, Captain Stewart agreed to transport Te Rauparaha and 100 warriors to the South Island.

Elizabeth arrived at Akaroa Harbour, on Banks Peninsula, home of Ngai Tahu's paramount chief Te Maiharanui. The northern warriors remained below deck, hidden from the unsuspecting southerners for several days. Eventually, Te Maiharanui, his young daughter, and later his wife, were welcomed aboard the ship by Captain Stewart, believing he wanted to negotiate a deal for a cargo of flax.

Once the chief was on board, Te Rauparaha and his warriors leaped from their hiding places and captured him. It’s said he was attached to the ship by a hook through the skin under his jaw, but it was a European crew member that first clamped the chief in irons. Unable to escape, Te Maiharanui could do nothing but listen to the screams of terror as northern warriors went ashore and killed his people.

Mission accomplished, Captain Stewart weighed anchor and sailed back to Te Rauparaha’s home at Kapati Island, the prisoners still on board along with many baskets of the victims flesh for feasting on. During the voyage, Te Maiharanui managed to kill his own daughter, rather than see her fall into enemy hands. When Te Rauparaha discovered this he was consumed with anger and as soon as they reached Kapiti Coast, he handed his captives over to the wives of the chief’s earlier killed at Kaiapoi, who slowly and cruelly tortured the southern chief and his wife to death.

By 1830, Guard had established one of the first shore whaling stations in New Zealand. Migrating whales came into Cloudy Bay and were close enough in for men to take to their whale boats, frantically row out to the whale, kill it, and tow it back to shore. Whalers settled at Cloudy Bay for the whale season where they worked hard and played hard.

Several trading ships were in the area seeking flax but finding it increasingly difficult to secure a cargo. The Maori either refused to trade or had upped the price expected in return. Captains become frustrated at the prospect of returning to Sydney empty with no profit and the prospect of a mutinous crew. Into the mix of difficulty acquiring flax and a warrior chief bent on revenge, sailed Captain John Stewart and his brig Elizabeth. In return for a cargo of flax, Captain Stewart agreed to transport Te Rauparaha and 100 warriors to the South Island.

Elizabeth arrived at Akaroa Harbour, on Banks Peninsula, home of Ngai Tahu's paramount chief Te Maiharanui. The northern warriors remained below deck, hidden from the unsuspecting southerners for several days. Eventually, Te Maiharanui, his young daughter, and later his wife, were welcomed aboard the ship by Captain Stewart, believing he wanted to negotiate a deal for a cargo of flax.

Once the chief was on board, Te Rauparaha and his warriors leaped from their hiding places and captured him. It’s said he was attached to the ship by a hook through the skin under his jaw, but it was a European crew member that first clamped the chief in irons. Unable to escape, Te Maiharanui could do nothing but listen to the screams of terror as northern warriors went ashore and killed his people.

Mission accomplished, Captain Stewart weighed anchor and sailed back to Te Rauparaha’s home at Kapati Island, the prisoners still on board along with many baskets of the victims flesh for feasting on. During the voyage, Te Maiharanui managed to kill his own daughter, rather than see her fall into enemy hands. When Te Rauparaha discovered this he was consumed with anger and as soon as they reached Kapiti Coast, he handed his captives over to the wives of the chief’s earlier killed at Kaiapoi, who slowly and cruelly tortured the southern chief and his wife to death.

|

This event was a sorry affair for Ngai Tahu, they now lived in constant dread of Te Rauparaha returning, and it was a fear well founded. Not content with killing the tribe’s paramount chief, Te Rauparaha was now intent on wiping out the entire tribe. His next raid was back to the stronghold of Kaiapoi and after a lengthy siege he overtook the pa, killing many people inside. Those who survived fled across the hills to Banks Peninsula but still they couldn’t escape the wrath of the northern chief.

His final assault was on the tiny peninsula inside Akaroa Harbour, Onawe. There a fort had been quickly built to defend the region’s remaining Maori. When Te Rauparaha’s war canoes entered the harbour everyone fled to the safety of the fortified pa. |

Seeing that they had access to food and water, Te Rauparaha realised a siege would not work here, so he set about preparing his final plan. Using survivors taken prisoner from Kaiapoi as decoys, Te Rauparaha lured some of the bewildered Ngai Tahu out. Once the gates were open and defenses down his warriors set upon the pa, killing everyone inside. Only a handful of people survived by fleeing into the hills, and for some time after this, Banks Peninsula was depopulated.

The power of Ngai Tahu now shifted to the chiefs in the south of the South Island, Te Whakataupuka and Tuhawaiki. A fort was built on Ruapuke Island in Foveaux Strait, and the tribe made preparations to defend themselves against Te Rauparaha’s imminent attack. Young women and children that had survived Te Rauparaha’s raids were sent south for protection while the men set about arming themselves. Muskets were in huge demand, and were traded between whalers and Maori.

The power of Ngai Tahu now shifted to the chiefs in the south of the South Island, Te Whakataupuka and Tuhawaiki. A fort was built on Ruapuke Island in Foveaux Strait, and the tribe made preparations to defend themselves against Te Rauparaha’s imminent attack. Young women and children that had survived Te Rauparaha’s raids were sent south for protection while the men set about arming themselves. Muskets were in huge demand, and were traded between whalers and Maori.

|

Settling down

About this time John Lidiard met his future wife, Kearaki, at Banks Peninsula. His protection meant she was safe from the prospect of a violent death at the hands of the northern warriors. Kearaki sailed south with John as he worked his way around the South Island. Almost all whaling ventures were now shore based, with only the Americans still participating in deep sea whaling. The Weller brothers from Australia built a large shore station in Otago. Sadly almost as soon as it was complete, the entire station burned to the ground and had to be rebuilt. Shortly after this, Tuhawaiki, known as Bloody Jack to the Europeans, rallied his men, headed north and defeated Te Rauparaha. It was a momentous occasion for the southern Maori who had lived in constant fear of the northern chief for many years. The war was not over as long as Te Rauparaha still lived, and although he’d literally managed to slip through one man’s fingers during battle, they now knew he was far from invincible. |

The whalers continued their move south as more ventures started out from Australia. One such entrepreneur was Johnny Jones. Jones took over Preservation station in southern Fiordland, established about the same time as Jacky Guard’s Cloudy Bay station. From there, Jones began setting up several smaller shore stations scattered around the southern coast and islands. This drew whalers from the north and across the Tasman and by the mid 1830’s various communities began to form. Life between southern Maori and Europeans was at times strained but mostly they lived and worked together as friends, and family. Some settlers obtained land deeds from the Maori, and others settled down with their wives in the hope of enjoying a quieter life.

About 1835, aged 46, John set up residence at the Bluff settlement started many years earlier by James Spencer. Spencer had been another early arrival at the Bay of Islands. His ship Cossack was wrecked at Hokianga, and he and his fellow survivors walked for five days in search of help. James Spencer worked for the mission station in return for his keep until he could get passage back to Sydney. However he became embroiled in mission station politics and was refused passage on the next available ship. Being no longer under the care of the mission Spencer was forced to sleep on the beach until he was able to stow away.

Living at Bluff, John worked at Johnny Jones’s Stirling Point station, managed by its namesake William Stirling. These were the good years for John and his friends. They taught their Maori wives to cook, clean, and sew in the European fashion and to grow gardens around the houses. The girls learned quickly and took great pride in keeping their house shipshape for their hard working husbands. The sea was teaming with whales and whaling ships, many of which called into Bluff. The number of American vessels visiting climbed rapidly, and the settlers were a colourful band of men that welcomed almost anyone into their fold. Rum flowed; as did stories of life at sea and in the old country.

About 1835, aged 46, John set up residence at the Bluff settlement started many years earlier by James Spencer. Spencer had been another early arrival at the Bay of Islands. His ship Cossack was wrecked at Hokianga, and he and his fellow survivors walked for five days in search of help. James Spencer worked for the mission station in return for his keep until he could get passage back to Sydney. However he became embroiled in mission station politics and was refused passage on the next available ship. Being no longer under the care of the mission Spencer was forced to sleep on the beach until he was able to stow away.

Living at Bluff, John worked at Johnny Jones’s Stirling Point station, managed by its namesake William Stirling. These were the good years for John and his friends. They taught their Maori wives to cook, clean, and sew in the European fashion and to grow gardens around the houses. The girls learned quickly and took great pride in keeping their house shipshape for their hard working husbands. The sea was teaming with whales and whaling ships, many of which called into Bluff. The number of American vessels visiting climbed rapidly, and the settlers were a colourful band of men that welcomed almost anyone into their fold. Rum flowed; as did stories of life at sea and in the old country.

|

In 1837, the northern Ngati Toa tribe through their allies Ngati Tama, made their last assault on Ngai Tahu. Traveling down the West Coast of the South Island, they made their way south and attacked the southern tribe at Bluff. The southerners defended well and were victorious over the northern intruders, capturing several slaves, one of which was given to a new settler.

The Maori were jubilant and the whalers filled with relief. This was to be the last battle in the south, and eventually Te Rauparaha’s own son, a Christian convert, visited the area to help negotiate an end to hostilities between the two tribes. In July 1837, Kearaki gave birth to a baby girl, Ann, known as Nancy. It was a dangerous time to begin life as disease from visiting boats began to plague the Maori. Over the next few years many Maori died from measles. While losing their lives, they were also losing their land, selling huge tracts to whalers and settlers, something both parties would feel the repercussions of in future years. |

A new vocation

The outside world of commercialism and development was finally catching up with the hardy band of settlers who had for so long enjoyed their own space and managed their own lives in the south. More boats arrived, one bringing new settler John Howell who set up a station at Jacob’s River, now known as Riverton. Officials began visiting too, and in June 1840, HMS Herald arrived to collect signatures for the Treaty of Waitangi. At Ruapuke Island three chiefs Tuhawaiki, Kaikoura, and Taiaroa signed the treaty. Tuhawaiki and one of his men wore uniforms they’d acquired in Sydney. Then came Stirling’s boat Success, with the first white women and child to settle in the south.

In 1843, whale exports halved and whaling stations began to close. The wholesale indiscriminate slaughter of whales had caught up with the whalers, just as it had with the sealers at the turn of the century. Having exhausted the source of their income, the heydays of whaling were well and truly over.

In early 1844, Bishop Selwyn arrived in Foveaux Strait, visiting all of the communities to perform marriages and baptisms. On 04 February at James Spencer’s house, Bishop Selwyn married John Lidiard to Kearaki. John signed his name on the register. William Stirling also married his partner, and six children were baptised. Visitors to Bluff were impressed with the community that had developed there, but the settlement's days were numbered.

The outside world of commercialism and development was finally catching up with the hardy band of settlers who had for so long enjoyed their own space and managed their own lives in the south. More boats arrived, one bringing new settler John Howell who set up a station at Jacob’s River, now known as Riverton. Officials began visiting too, and in June 1840, HMS Herald arrived to collect signatures for the Treaty of Waitangi. At Ruapuke Island three chiefs Tuhawaiki, Kaikoura, and Taiaroa signed the treaty. Tuhawaiki and one of his men wore uniforms they’d acquired in Sydney. Then came Stirling’s boat Success, with the first white women and child to settle in the south.

In 1843, whale exports halved and whaling stations began to close. The wholesale indiscriminate slaughter of whales had caught up with the whalers, just as it had with the sealers at the turn of the century. Having exhausted the source of their income, the heydays of whaling were well and truly over.

In early 1844, Bishop Selwyn arrived in Foveaux Strait, visiting all of the communities to perform marriages and baptisms. On 04 February at James Spencer’s house, Bishop Selwyn married John Lidiard to Kearaki. John signed his name on the register. William Stirling also married his partner, and six children were baptised. Visitors to Bluff were impressed with the community that had developed there, but the settlement's days were numbered.

|

Stirling’s ship Success was totally wrecked at Bluff after the crew had spent the evening in Spencer’s pub. The 40 odd settlers were now hard pressed to make a living as few ships called, and in 1846 the original settler, James Spencer, died at sea while returning from Sydney. It was the beginning of the end for the little community. John Lidiard continued to live at Bluff until the death of his wife Kearaki after which he moved with his daughter to Jacob’s River to work for Captain Howell, the Jacob’s River settlement thriving with 70 or 80 residents.

In later years, a little school in the district was opened and John gathered up the children who until now had enjoyed a free run. Captain Howell’s son George later said of his teacher "Morally and spiritually he was a good teacher and a good leader. Frequently he would lecture us on our duties to one another and always he stressed the necessity for telling the truth.....He was always dignified. In fact, he set great store upon personal dignity, and he was thorough in all that he undertook. He was a fine man." At the age of 14, John’s daughter Nancy traveled to Ruapuke Island to marry James Lee, the son of John Lee, who had also been in the Bay of Islands in the early years. Within three years James had died and in 1854, Nancy married the son of another new settler Edward Stevens. A short time later while Nancy was pregnant with their child, Edward lost his life too. Two times a widow by the age of 19 and an unmarried expectant mother, these were heartbreaking times for John and his daughter. Two years later, Nancy met her third husband William Thomas and together they raised her only child Edward Stevens. |

The end

Progress marched on. Immigrant ships arrived, communities turned into towns, roads turned into streets, and a new nation formed before John's eyes. Having outlived all of his contemporaries, on 09 January 1876, John Lidiard - ship boy, Jack Tar, whaler, Pakeha Maori, husband, father, settler, teacher, survivor - died at his daughter's home at the age of 86.

Before he died, a companion sat with John while he recounted the story of his incredible life, so that it could be captured and remembered. That document, remains undiscovered and perhaps, forever lost in time.

Progress marched on. Immigrant ships arrived, communities turned into towns, roads turned into streets, and a new nation formed before John's eyes. Having outlived all of his contemporaries, on 09 January 1876, John Lidiard - ship boy, Jack Tar, whaler, Pakeha Maori, husband, father, settler, teacher, survivor - died at his daughter's home at the age of 86.

Before he died, a companion sat with John while he recounted the story of his incredible life, so that it could be captured and remembered. That document, remains undiscovered and perhaps, forever lost in time.

|

Inscription on John Lidiard's headstone

"In loving memory of Ann Thomas who died 26th April 1900 aged 63 years. Also John Clark Lidiard who died 1877 aged 88 years (sic). Also William Thomas died 5th October 1903 aged 68 years. Also George de Paravicini, beloved son of John and Emma Simon born 10th September, died 30th December 1873." |